The urban environment presents dangers to wildlife that they are not always adapted to overcome. Reducing urban hazards is an essential part of enhancing habitat in cities. After all, we do not want to lure wildlife into our neighborhoods only to have them fatally collide with our windows.

1. Keep cats indoors

If you have a cat in your life, the most important thing you can do for urban wildlife, and for the health of your kitty friend, is to keep it inside.

Outdoor, free-roaming cats kill are estimated to kill an average of 2.4 billion birds per year in the United States, and an even larger number of small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians (Loss et al. 2013). This makes cats the leading cause of direct, human-related bird mortality.

Keeping your cat inside is also good for your cat.

Indoor cats live 3-5 times longer than outdoor cats, as they are less susceptible to disease and parasites and are not as likely to be exposed to poisons, pesticides, traffic, or attacks from predators like dogs or coyotes. The negative impacts to wildlife and the cats themselves is why the American Veterinary Medical Association advises cat guardians to keep cats indoors.

Keeping cats indoors does not necessarily lead to behavior issues.

Learn how to keep your cat happy indoors. You can also provide safer outdoor stimulation to your cat with outdoor enclosures (or “catios”—cat patios) and leash training.

2. Make windows safe for birds

Birds behave as if they cannot see glass. Reflections of sky or habitat in windows may appear to birds as an extension of the environment and they frequently collide with them at high speed.

In fact, nearly one billion birds may be killed each year in the United States due to collisions with structures, making collisions the second worst human-related threat that directly kills birds (only outdoor, free-roaming cats cause more direct bird-mortality).

In the Seattle area, more than 80 bird species are documented colliding with windows.

This includes species, like the Varied Thrush, that have already experienced steep population declines and are also vulnerable to climate change.

Some wildlife rehabilitators estimate that greater than 80% of birds that seem to recover from collisions eventually die from their injuries, even if they appear to have recovered and fly away. Reducing collision risk to birds is important to help us keep common birds common and to prevent threatened birds from going extinct. Bird-window collisions can be prevented with collision deterrents, like the Feather Friendly™ vinyl film dots applied to the outside of a window.

Reducing bird-window collision is easy in concept: help birds see and avoid glass.

This is usually done by adding “visual noise” to the exterior surface of windows to break up window reflections and make the window appear as a barrier. There are many ways to do this. It can be as simple as using a bar of soap to draw lines on a window, making collision deterrents out of paracord, and applying pre-made window treatments. You can even get artistic with it!

Learn more at Seattle Audubon: Preventing Bird-window Collisions

3. Reduce or eliminate pesticide use

Pesticides are chemicals used to manage organisms people consider pesky, such as rats, mosquitos, and weeds. Some pesticides harm bees that help pollinate plants. Some kill beneficial insects that birds and other wildlife depend on for food. Some pesticides enter the food web and can poison unintended species.

In Capitol Hill, one of the biggest pest pressures is from rodents. A common rat control strategy is to poison them, often with chemicals called anticoagulant rodenticides (ARs).

ARs are highly toxic but slow acting, allowing rodents to consume multiple doses before they succumb to poisoning. SGARs do not readily break down into non-toxic components after they have been ingested and can be stored in the tissues of an animal. If a hawk eats a poisoned rat, the hawk also ingests the poison stored within the rat. This can have negative impacts on the hawk’s fitness, and if the hawk continues to eat poisoned rodents, it may eventually become poisoned itself.

ARs have been detected in more than 100 non-target species, including 70 bird and 40 mammal species (Eckle et al. 2020), and have caused an untold number of secondary wildlife poisoning incidents.

Research by the Urban Raptor Conservancy in the Puget Sound region detected SGARs in the overwhelming majority of dead hawks and owls that the team recovered (Urban Raptor Conservancy, 2020). The level of accumulation in the food web and the negative impacts it causes has led some to compare today’s AR use to that of DDT in the mid-1900s.

4. Reduce artificial light at night

A lot of organisms—including many that occur in Seattle—are nocturnal, meaning they are active at night and adapted to life in the dark. For nocturnal creatures, darkness is a critical part of their habitat, important for their ability to avoid predators, to find prey, and to regulate the natural rhythms of their lives.

In cities, real darkness is hard to come by. Everything, it seems, is illuminated. Streets, ball fields, parking lots, communication towers, high-rises, and porches. And we tend to keep the lights burning all night long. Skies over cities can be hundreds of times brighter than a natural, starlit sky. This artificial light at night, which has only appeared very recently in the long evolutionary history of species, can drastically disrupt, disorient, confuse and otherwise harm many nocturnal animals.

Artificial light at night is known to attract night-flying migratory birds into urban areas where they can become disoriented, exhausted, and vulnerable to window collisions or cat predation.

Learn more about birds and artificial light at night at BirdCast.

Artificial light at night is also harmful to many nocturnal insect species. Like birds, artificial light at night can act like a beacon and attract insects. Some insects will be lured to their deaths around bulbs, some will become easily visible to predators, and some will be disrupted from or distracted from important insect business, like mating.

Read more about protecting nocturnal insects by turning off lights.

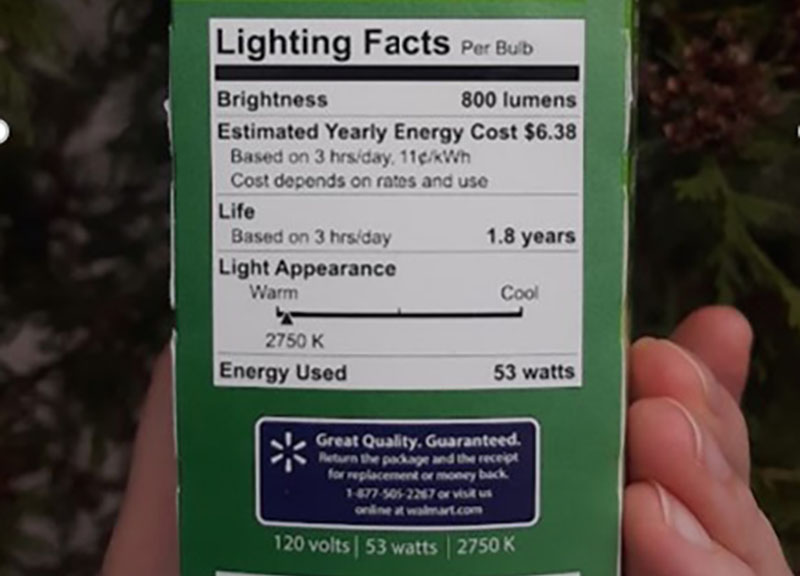

Reducing artificial light is something we all have some direct control over. At night, use blinds and curtains to minimize the amount of light that leaks out of your windows. Turn lights off when they are not in use. Shield outside lights to strategically direct it where you need it to prevent light from escaping upward. And use “warm” lights—bulbs that have a warmth of 3000 kelvins or less. And support Lights Out programs and building design policies that require new developments to limit light that escapes into the sky.

5. Control and clean up trash

Trash is seemingly everywhere in the cities. It escapes from garbage bins on collection day, collects near storm drains, piles up at illegal dumping areas or at sites without trash collection services. Trash can be hazardous to wildlife if they consume it, if they become tangled in it, or if it provides food resources to rodents.

Make sure your outdoor trash, recycle, and compost bins shut securely and avoid overfilling them. If trash escapes your collection bins, clean it up quickly. If you need to throw away an item at a park but garbage cans are full or overflowing, hold onto any items until you find a bin that can properly contain the trash.

A lot of trash enters Puget Sound, Lake Washington, and Lake Union through storm drains that empty directly into these water bodies. Trash in our waterways threatens many marine and aquatic species. Consider adopting a storm drain, to help keep it clear and to prevent trash from entering the drain.

6. Incorporate green stormwater infrastructure

Has anyone noticed that it rains frequently in Seattle? Where does the rain go after it falls on our streets? Eventually it ends up in Puget Sound.

Stormwater runoff is a major cause of water pollution in Puget Sound, Lake Washington, and Lake Union. Green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) can help slow and filter stormwater where it falls. GSI includes permeable pavements, rain gardens, bioretention systems, living walls, cisterns, trees, planters, bioswales, and other interventions that involve natural hydrological processes. GSI mitigates the impact of stormwater runoff, which carries streetscape and sewage waste into waterways.

Trees are an efficient tool for GSI, effective at retaining rainwater and preventing erosion and runoff. Other vegetation, like native shrubs, are also useful for GSI, providing a large surface area on the leaves to intercept, hold, and evaporate moisture before it hits the ground.

A good way to add to the city’s GSI is by building rain gardens containing soils with a high capacity for saturation.

Learn more

7. Provide nesting opportunities

A lot of birds, like northern flickers, excavate holes in dead standing tress and build nests inside. Other cavity nesters, like black-capped chickadees, rely on holes excavated by woodpeckers. In our neighborhoods, though, there are not many dead standing trees. We can supplement nesting opportunities for cavity-nesting birds with nest boxes.

Nest Boxes

A lot of birdhouses and nest boxes commercially available are cute but don’t always serve birds well. Nest boxes should avoid bright colors; remember, birds are protecting their vulnerable eggs and young, and bright colors can more easily attract attention from predators. Perches can also be detrimental; birds don’t need them and they can help predators get inside. Further, different bird species have their own specifications for what they consider a good hole for nesting. Wrens and chickadees like very small holes (1 1/8-inch diameter), while screech owls need a three-inch-diameter hole.

Mason Bees

Mason bees are a small, harmless type of bee that emerge in early spring. They are efficient pollinators and, like some birds, nest in cavities or tunnels. A lot of people enjoy attracting and supporting mason bees with mason bee nest boxes. They are very simple to construct and are also readily available online.