The plants, animals, fungi, microbes, and other natural features that make up urban habitat are important to the character, function, and livability of cities. Read on to learn about biodiversity and urban habitat, explore what makes urban habitats different from other types of habitats, and review the benefits urban habitats provide to people.

What is urban habitat?

“Habitat” refers to all the living and nonliving components of an area that provide the resources to support the survival and reproduction of a particular organism.

This could include soil; light intensity; temperature; moisture; as well as other organisms such as plants, insects, etc. Habitats are specific to the kinds of plants or animals that live there. A sword fern has different habitat needs from a bumblebee, which has different needs from a salmon.

Urban habitats are areas that provide these resources for plants and animals in cities. Perhaps the most obvious are Seattle’s large, mostly natural areas, like Discovery Park. But urban habitats can be found in surprising places. For example, rooftops in the Industrial District serve as a nesting substrate for birds like Caspian terns. Potted plants on balcony gardens can support the habitat needs of insects and birds. Parks; cemeteries; vacant lots; golf courses; landfills; yards; potted plants; gardens; street trees; and lakes, streams, and rivers within a city’s boundaries all provide urban habitat with varying degrees of quality.

How are urban habitats different from habitats that are less influenced by people?

There are many different types of urban habitat. But they tend to share a few characteristics.

Urban habitats are often heavily managed and dominated by human uses

Urban habitats are situated within or in close proximity to large population centers and areas of dense development. The habitats are usually managed for human uses.

For example, parks tend to be managed primarily for recreation; an apartment’s landscaping for aesthetics and ease of maintenance; and street trees to avoid interfering with overhead power lines, other utilities, and traffic. The needs of plants and animals don’t always influence how urban habitats are managed.

Urban habitat tends to consist of many small, fragmented habitat patches

In cities, land has been divided and subdivided into thousands or hundreds of thousands of different parcels, lots, and properties.

In the process, the habitats and natural features that may have once been large, continuous expanses become fragmented into many smaller pieces disconnected from each other. This tends to result in smaller habitat patches, with less “interior” habitats and more “edge” habitats. Species that rely on interior habitats can be lost as a result of habitat loss and fragmentation.

This loss of interior species has occurred in Seattle and within the Biodiversity Corridor. Prior to the arrival of colonial settlers, the Capitol Hill, First Hill, and Central District neighborhoods were part of an extensive upland conifer forest dominated by Douglas fir, western hemlock, and western red cedar. Big predators like grizzly bears wandered through, elk visited, and spotted owls hooted from the trees.

Today, the large native conifers that used to dominate the area are mostly gone, and so are the grizzlies, elk, and spotted owls. Deciduous trees—including maple, cherry, plum, ash, and many others—make up the majority of the tree canopy in the neighborhoods. Cats seem to be the most abundant big predators, and rabbits are usually the largest herbivores.

Urban habitats tend to contain “novel biological assemblages.”

In cities, great numbers of people, ideas, interests, and motivations mix. As people move to urban spaces, they sometimes bring with them plants and animals from other regions, countries, and continents. This creates new communities of plants and animals that have not previously been in contact.

Today, Seattle’s birds forage in hundreds of different tree species, while, prior to urbanization, there were just a few dozen. Our bees buzz between blossoms from Europe, Asia, Australia, and South America. The new arrangements may provide benefits to some urban wildlife, but sometimes the interactions are harmful.

Benefits of urban nature

Trees, vegetation, and other natural features and processes are important to the quality of life, health, and well-being of city dwellers—human and beyond.

Urban nature reduces stress and improves health

Nature is a stress reliever. Researchers have found that experiences with nature—even just for 10 minutes—can reduce the level of the stress hormone cortisol in the body (Hunter et al., 2019). Another study shows that greater amounts of green space in the neighborhood in which a person lives is correlated with lower cortisol levels and lower self-reports of stress (Thompson et al., 2012). Nature also improves health. To take just one example, trees and vegetation reduce temperatures and the impact of heat on urban residents, which reduces the risk of cardiovascular-disease-related mortality (Van den Bosch et al., 2017).

Urban nature helps us mitigate and adapt to climate change

Integrating nature into our cities can improve climate resilience for human communities, while development practices that remove habitat and create more impervious surfaces expose us to greater risks of flooding, high heat, pollutants, and other climate impacts.

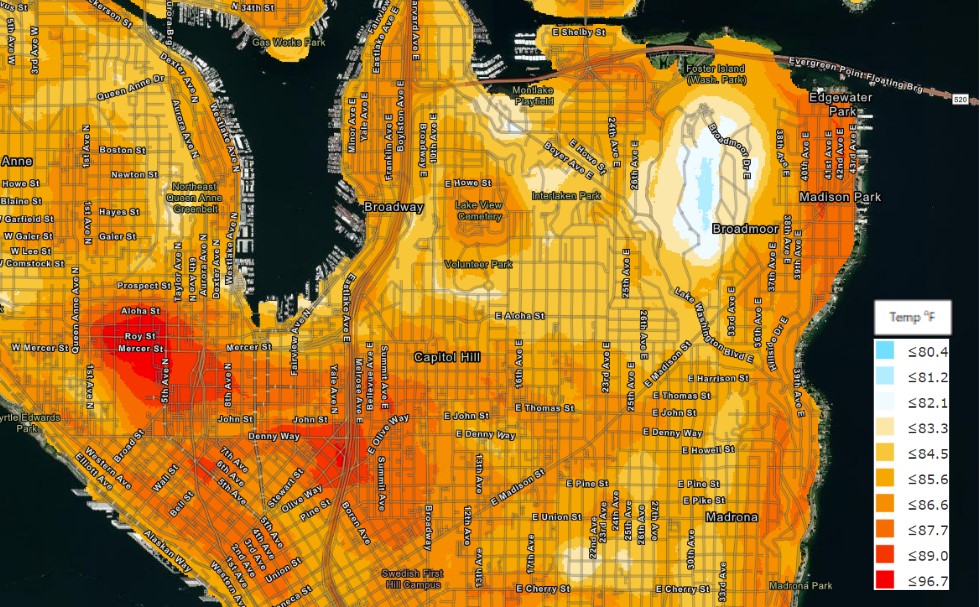

The trees and vegetation in our urban forest will play an important role in how our neighborhoods adapt to climate change. They are often the first line of defense against extreme heat, winds, and rain. A King County heat mapping study found that highly urbanized areas with fewer trees and less vegetation were 23 degrees Fahrenheit hotter in the evening than areas with more natural land cover. In figure 6 below, compare the evening heat model in south Capitol Hill to the heat model at the Washington Park Arboretum. A healthy, growing, and equitably distributed urban forest is important for community climate resilience.

In Washington State, human-caused climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme heat days (Philip et al., 2021). It is also increasing incidences of wildfires and causing changes in forest composition and distribution. Earlier melting of snowpack can affect the timing of wildflower blooms in alpine areas (Breckheimer et al., 2019). This all has the potential to disrupt resource availability to birds, pollinators, and other wildlife. In cities, vegetation can be monitored and managed more deliberately. If we thoughtfully plant urban areas with a diversity of plant species and manage them for resilience, urban habitat may be able to offer stable, abundant year-round resources to birds and pollinators.

Urban nature helps us recreate

Urban nature provides opportunities for recreational activity outdoors. For example, forty-five million people across the United States participate in bird-watching (Carver, 2019) and many others enjoy hiking, running, botanizing, foraging, bushcraft, etc. Thousands of bird watchers train their binoculars on Seattle’s urban birds every year, and many thousands more visit parks for kayaking, swimming, and paddleboarding on the lakes, Sound, and other waterways.

The parks along the 11th Avenue Biodiversity Corridor are essential community assets. Most residents in the surrounding neighborhoods are renters without access to private yards. Public parks help fill the need for outdoor spaces to relax and recreate.

Urban nature has economic benefits

Urban nature can have economic benefits. The presence of large trees in yards or along streets can increase neighborhood home values from 3 to 15 percent (Wolf, 2007). Homes adjacent to parks and open spaces are valued 8 to 20 percent higher than comparable properties (Crompton, 2001; Hammer et al. 1974; Tyrväinen & Miettinen 2000; More et al. 1988), and shoppers say they are willing to drive farther to visit business districts with quality trees, will spend more time there, and report spending 9 to 12 percent more (Wolf, 2005). Bird watchers spent $26 billion on equipment in 2016 for watching birds and an additional $10 billion to go on wildlife watching trips (Carver, 2019).

Where open space is limited, connectivity is crucial

Open spaces like parks, plazas, and campuses are essential community assets. In Capitol Hill, spaces like Volunteer Park, Cal Anderson Park, and the Seattle University campus provide space for people to gather, feel supported by their communities, and be active.

Seattle neighborhoods are continuously adapting to population growth, redevelopment, and changes in housing density and affordability. As urbanization and population density increases, neighborhood greenery can be lost. This increases the need for and demands on parks and and green space.

While there are numerous parks in Capitol Hill, First Hill, and the Central District, the overall area of park space per capita is low—fewer than 8 square meters available per person in all the neighborhoods surrounding the biodiversity corridor. This is four times lower than Seattle’s city-wide per capita amount of park space of about 32 square meters per person. For context, the World Health Organization recommends a minimum of 9 square meters of park space per person, and ideally 50 square meters of park space.

Where parks and public space are limited, like in the neighborhoods around the Biodiversity Corridor, it is important that all parks be accessible and easy for people to move between. With thoughtful additions to the right-of-way, sidewalks can function as pedestrian parkways and facilitate pedestrian and bicycle movement between parks.

We can improve connectivity between green space for people by adding places to sit along sidewalks, creating shelters from rain and sun, providing public bathrooms, adding wayfinding, maintaining sidewalks in good conditions, placing bike racks, creating public art, and adding to landscaping to promote enjoyment, comfort, lingering, interest, and easy fluidity from space to space.