New types of vegetation can attract additional wildlife to an area. You might be surprised how a little green can go a long way! Below are a few tips for adding new plants that support wildlife.

Find the right plant for the right space

Determining which tree or other plant species will work given available space and other growing conditions (e.g., sun/shade exposure, soil type, etc.) is critical for your new plant to survive and thrive in the long term. Learn more about right plant in the right place gardening and check out our wildlife-supporting plant guide for growing conditions.

We have assessed planting strips in the right-of-way for 124 block faces in the Biodiversity Corridor for sun/shade exposure, presence of overhead utilities, etc., which may be useful for choosing the right plant for the right space in this corridor. You can explore more on the interactive Biodiversity Corridor map.

Favor native plants

Native plants are those that evolved in and adapted to a particular location—in our case, the Puget Trough ecoregion. Plants native to the Puget Trough ecoregion are usually well suited for our climate and soil and provide good-quality resources to our local wildlife. Importantly, native plants are often better at supporting beneficial insects that form the base of the food chain for many other species.

Most land birds depend on insects to raise their young, and raising a young bird requires an astonishing number of insects. A biologist from the US Midwest observed Carolina chickadees feeding about 80 caterpillars to each of their chicks in a single day (Brewer, 1961). Given that chickadees have between 5 to 8 chicks at a time, it could take between 6,000 and 10,000 caterpillars just to fledge a single clutch of chickadees!

Clearly, if we want birds in our neighborhoods, we need bugs, too. Native plants tend to support a greater abundance and diversity of insects that support birds. Looking again at the Carolina chickadee, researchers found that their populations could not be sustained in areas where native plants composed less than 70 percent of the vegetation (Narango, 2018).

You can find wildlife-supporting plants that are native to Western Washington in our wildlife-supporting plant guide.

Create structural diversity

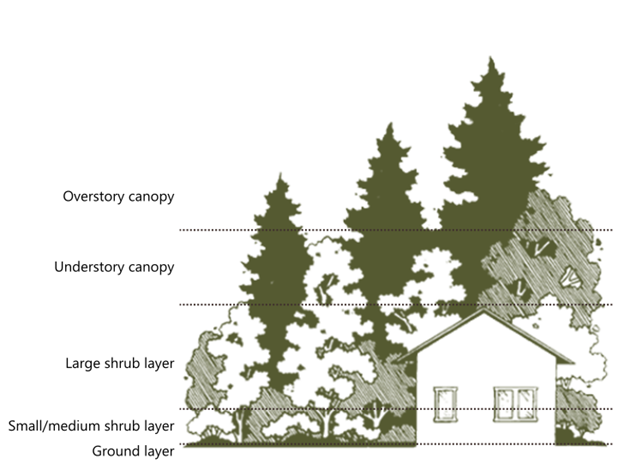

A healthy forest has layers: an overstory canopy, an understory canopy, a shrub layer, and a ground cover layer (see image below). Different wildlife species occupy different layers. Spotted towhees and song sparrows, for example, forage in the ground cover for insects. Anna’s hummingbirds nest in shrub layers and understory canopies, and eagles take advantage of the good views from the overstory canopy. Planting species that will grow to different sizes, from large to small, creates a diversity and complexity of structures and habitats that will benefit a wider diversity of urban wildlife.

Different layers of urban forest habitat. Adapted from WDFW Landscaping for wildlife by Russel Link

Consider the timing of blooms

If you are planting flowering plants, select species that bloom at different times. This provides year-round interest in your garden and helps provide year-round nectar and pollen resources for wildlife.

There are many types of beneficial insect pollinators, and each has its own life cycle. Some, like mason bees (Osmia spp.), emerge and are active in early spring when temperatures reach about 50 degrees Fahrenheit, usually between March and April in Seattle. They are active for about 8 to 10 weeks, then they button up shop in early summer. But early summer through fall is when our native bumblebees (Bombus spp.) are most abundant and active. Hummingbirds live in Seattle year-round and benefit from winter-blooming species like eucalyptus and mahonia. Ensuring the many different pollinators have an abundant supply of flowering plants to feed from all year long is important to supporting our urban pollinator diversity.

Prioritize planting in areas that help connect habitat patches

Connecting fragmented or isolated habitat patches makes it easier for wildlife to move between and among habitat to access food and other resources. Filling in gaps between different patches can help improve habitat values for wildlife. In fact, that’s one of the primary goals of this of the Urban Biodiversity Corridor!

Plant with climate change in mind

Human-caused climate change is already impacting Seattle, bringing hotter, drier summers; more extreme heat days; and more intense rainfall events. As climate changes, so will the vegetation that can thrive here.

You may wish to seek and plant drought- and heat-tolerant plants, such as California lilac (Ceanothus spp.)— not a true lilac, though from a distance, its flowers can resemble lilac splays. California lilac is often heat tolerant, salt tolerant, and drought tolerant. And the bush attracts pollinators by the hundreds in the spring.